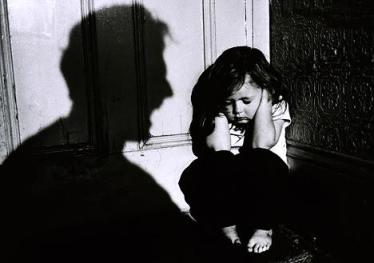

Reporting Suspected Child Maltreatment: Legal and Ethical Issues is a new 2-hour video continuing education (CE) course that outlines the legal requirements for reporting suspected child neglect and abuse.

Many professionals throughout the United States are mandated reporters of suspected child maltreatment. However, the legal requirement to report is often confusing to navigate in relation to other professional and ethical responsibilities. This workshop provides profession-based context to the role of mandated reporter.

The course opens with a brief history of mandated reporting and the changes to mandated reporting laws over time. We then discuss who is considered a “mandated reporter,” when a report to Child Protective Services (CPS) is necessary, and the concerns regarding under and over reporting.

A detailed discussion highlights the risk factors and indicators of maltreatment and provides specific definitions and examples of the four types of maltreatment (neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse).

Mandated reporters explore a framework that can guide their decision in making the “tough call” of whether to file a report to CPS or not, using research findings and practical advice based on real case examples. Course #21-56 | 2022 | 2-hour video & handout | 20 posttest questions

Click here to learn more about Reporting Suspected Child Maltreatment

- CE Credit: 2 Hours

- Target Audience: Psychologists | Counselors | Social Workers | Occupational Therapists (OTs) | Marriage & Family Therapists (MFTs) | Nutritionists & Dietitians | School Psychologists | Teachers

- Learning Level: Introductory

- Course Type: Video

Reporting Suspected Child Maltreatment is an online course that provides instant access to the course materials (PDF download) and CE test. The course is text-based (reading) and the CE test is open-book (you can print the test to mark your answers on it while reading the course document).

Successful completion of this course involves passing an online test (80% required, 3 chances to take) and we ask that you also complete a brief course evaluation. Click here to learn more.

About the Author:

Kathryn Krase, PhD, JD, MSW, is the principal consultant and owner of Krase Consulting, a multi-disciplinary consulting firm with experience in child welfare systems, higher education, non-profit management, and youth sports coaching. Dr. Krase is an expert on the professional reporting of suspected child maltreatment and has authored multiple books and articles on the subject. She has years of experience consulting with government and community-based organizations to develop policy & practice standards. As part of her extensive work to educate and support healthcare professionals to intervene and protect children, when necessary, while respecting and supporting family integrity whenever possible, Dr. Krase offers training, resources, blogs, podcasts, and consultations through her website, Making the Tough Call.

Professional Development Resources is approved by the American Psychological Association (APA) to sponsor continuing education for psychologists. Professional Development Resources maintains responsibility for this program and its content. Professional Development Resources is also approved by the National Board of Certified Counselors (NBCC ACEP #5590); the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB Provider #1046, ACE Program); the Continuing Education Board of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA Provider #AAUM); the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA Provider #3159); the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR Provider #PR001); the Alabama State Board of Occupational Therapy; the Arizona Board of Occupational Therapy Examiners; the Florida Boards of Social Work, Mental Health Counseling and Marriage and Family Therapy, Psychology and Office of School Psychology, Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, Dietetics and Nutrition, and Occupational Therapy Practice; the Georgia State Board of Occupational Therapy; the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners – Occupational Therapy; the Mississippi MSDoH Bureau of Professional Licensure – Occupational Therapy; the New York State Education Department’s State Board for Psychology as an approved provider of continuing education for licensed psychologists (#PSY-0145), State Board for Mental Health Practitioners as an approved provider of continuing education for licensed mental health counselors (#MHC-0135) and marriage and family therapists (#MFT-0100), and the State Board for Social Workers an approved provider of continuing education for licensed social workers (#SW-0664); the Ohio Counselor, Social Worker and MFT Board (#RCST100501) and Speech and Hearing Professionals Board; the South Carolina Board of Examiners for Licensure of Professional Counselors and Therapists (#193), Examiners in Psychology, Social Worker Examiners, Occupational Therapy, and Examiners in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology; the Tennessee Board of Occupational Therapy; the Texas Board of Examiners of Marriage and Family Therapists (#114) and State Board of Social Worker Examiners (#5678); the West Virginia Board of Social Work; the Wyoming Board of Psychology; and is CE Broker compliant (#50-1635 – all courses are reported within a few days of completion).

Enjoy 20% off all online continuing education (CE/CEU) courses @pdresources.org! Click here for details.