As two national organizations committed to working to empower the autism and Autistic communities today and into the future, the Autism Society of America and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network issue the following joint statement regarding the definition of Autism Spectrum Disorder within the DSM-5.

As two national organizations committed to working to empower the autism and Autistic communities today and into the future, the Autism Society of America and the Autistic Self Advocacy Network issue the following joint statement regarding the definition of Autism Spectrum Disorder within the DSM-5.

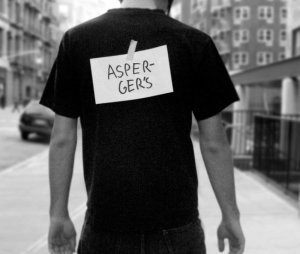

The autism spectrum is broad and diverse, including individuals with a wide range of functional needs, strengths and challenges. The DSM-5’s criteria for the new, unified autism spectrum disorder diagnosis must be able to reflect that diversity and range of experience.

Over the course of the last 60 years, the definition of autism has evolved and expanded to reflect growing scientific and societal understanding of the condition. That expansion has resulted in improved societal understanding of the experiences of individuals on the autism spectrum and their family members. It has also led to the development of innovative service-provision, treatment and support strategies whose continued existence is imperative to improving the life experiences of individuals and families. As the DSM-5’s final release approaches and the autism and Autistic communities prepare for a unified diagnosis of ASD encompassing the broad range of different autism experiences, it is important for us to keep a few basic priorities in mind.

One of the key principles of the medical profession has always been, “First, do no harm.” As such, it is essential that the DSM-5’s criteria are structured in such a way as to ensure that those who have or would have qualified for a diagnosis under the DSM-IV maintain access to an ASD diagnosis. Contrary to assertions that ASD is over diagnosed, evidence suggests that the opposite is the case – namely, that racial and ethnic minorities, women and girls, adults and individuals from rural and low-income communities face challenges in accessing diagnosis, even where they clearly fit criteria under the DSM-IV. Furthermore, additional effort is needed to ensure that the criteria for ASD in the DSM-5 are culturally competent and accessible to under-represented groups. Addressing the needs of marginalized communities has been a consistent problem with the DSM-IV.

Individuals receive a diagnosis for a wide variety of reasons. Evidence from research and practice supports the idea that enhancing access to diagnosis can result in substantial improvements in quality of life and more competent forms of service-provision and mental health treatment. This is particularly true for individuals receiving diagnosis later in life, who may have managed to discover coping strategies and other adaptive mechanisms which serve to mask traits of ASD prior to a diagnosis. Frequently, individuals who are diagnosed in adolescence or adulthood report that receiving a diagnosis results in improvements in the provision of existing services and mental health treatment, a conceptual framework that helps explain past experiences, greater self-understanding and informal support as well as an awareness of additional, previously unknown service options.

Some have criticized the idea of maintaining the existing, broad autism spectrum, stating that doing so takes limited resources away from those most in need. We contend that this is a misleading argument – no publicly funded resource is accessible to autistic adults and children solely on the basis of a diagnosis. Furthermore, while the fact that an individual has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder does not in and of itself provide access to any type of service-provision or funding, a diagnosis can be a useful contributing factor in assisting those who meet other functional eligibility criteria in accessing necessary supports, reasonable accommodations and legal protections. As such, we encourage the DSM-5 Neurodevelopmental Disorders Working Group to interpret the definition of autism spectrum disorder broadly, so as to ensure that all of those who can benefit from an ASD diagnosis have the ability to do so.

The Autism Society and Autistic Self Advocacy Network encourage other organizations and groups to join with us in forming a national coalition aimed at working on issues related to definition of the autism spectrum within the DSM-5. Community engagement and representation within the DSM-5 process itself is a critical component of ensuring accurate, scientific and research-validated diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, our community must work both before and after the finalization of the DSM-5 to conduct effective outreach and training on how to appropriately identify and diagnose all those on the autism spectrum, regardless of age, background or status in other under-represented groups.

P.S. The Autism Society will continue to share its thoughts and feelings about keeping the community inclusive as more information about the revisions is known. In the meantime, we strongly encourage people to get involved in the discussion.

Related Articles:

- Proposed DSM 5 Changes and Autism: What Parents & Advocates Need to Know (pdresources.wordpress.com)

- MIXED EMOTIONS: A Mother and Son Response to the DSM-5 Change (autismspeaks.org)

- DSM-5 Autistic Spectrum Disorder Disaster By Kim Oakley Should Be Mandatory Reading For The DSM-5 Committees (autisminnb.blogspot.com)